My trip begins and ends in Accra, which is the capital of Ghana. Or it does if you do not count the cancellation of my flight out of Baltimore because of the weather in New York, which was rescheduled to National, apparently because the weather in New York would be better if I was coming from DC; or my endless ride on the bus between the terminals in JFK Airport in New York, where I concluded that if there is a hell, it is like JFK - all old concrete and steel buildings, endless roads and ramps curving around each other, packed with traffic, and all white lights and harsh noises; or my time inside the British Air terminal in New York, which is decorated in a style that is sort of a 90's take on what they thought the future would look like back in the 60's, only I'm sure that in the 60's they thought that the future would be cleaner than that; or my time in Heathrow, with its endless twisting tunnels between the plane and the terminal. But aside from all of that, my trip began in Accra.

I arrived at night, which is pretty much the only time that one can arrive in Accra, and my first impression of the City was the incredible disorganization of the airport, which was under construction. A fair reflection of a disorganized and under construction city. Fortunately I found Lisa, who I am here to visit, and Amadou, the driver for WANEP, which is the organization she works for, without problem. My next impression was that Accra was not terribly well lit. In the darkness I could see the typical markets in concrete boxes with steel doors along with endless lantern lit stands closer to the street, selling food, sundries or whatever else might sell, together with the masses of humanity walking by, stopping at the stands, hanging out, and generally giving it the vague air of a Grateful Dead parking lot. Among my other initial impressions are that it is hot, and a relief that they drive on the correct side of the road, since my guidebook (which I later realized was written in Britain) seemed quite convinced that they drove on the wrong side.

I am here to visit my friends Lisa and Bill, who are in Ghana doing peace work, and their daughter Miranda, who is two and a half. They live in Lashibi, which is technically a suburb of Tema, but expansion of Accra has turned this whole area of the coast into an undifferentiated megalopolis. Thus, my first day was actually spent in Lashibi, and in Teshie/Nungua, which is probably two separate places, but I never heard either of them said separately, and they, like Lashibi, have essentially been swallowed by Accra. That said, my first daylight impression of Accra, when I walked into Bill and Lisa's front yard, was that I was in Florida. The grass was the same, the plants were the same ones - bougainvillea, croton, hibiscus and so on - that are used in landscaping in Florida, and the architecture of the nearby houses was very similar - single story stucco houses in a somewhat Spanish style. Of course, I don't know of anywhere in Florida where every single house has a masonry wall around the perimeter of the yard. And the size of the lizards is different, since these are about five times the size of the average anole. The similarity of the vegetation is interesting. Of course, a lot of it is because the plants have been transplanted from one place to the other or from some other place to both. But some of them must be native to both. There is no reason that I know of to transplant something like a strangler fig from one place to another. And while there are, I suppose, reasons to transplant mangroves, I seem to remember reading that Cortez's men had to hack through them to get onto dry land in Florida.

The fences around every house also always amaze me, though they seem to be common around the world. Security consciousness is high here. I have not seen ground glass in the tops of the fences, but Bill and Lisa's house has locks on every door and on every section of the closets, and I later see the same thing in hotel rooms. There are also bars on the windows of most houses, and locked gates to get into many offices. Basically though, I feel that it is like the glass on the walls in Bolivia, not there because the actual threat is so high, but to deter any threat from arising. In fact, everything that I have read talks about how safe Ghana is, and I never feel threatened.

Bill and Lisa's house is large - three bedrooms, two baths, living room, dining area, a small kitchen, a garage and an additional area for the housekeeper. While the house is big, it is simple. The whole floor is ceramic tile, the walls plain, or ceramic in the kitchen and bathrooms. Lights are mostly bare bulb, fans plain. The fans are, however a life saver, since there is no air conditioning and the temperature is steadily hot. There is also the area where Juliette lives. Juliette is in charge of everything - cleaning, cooking, spider-killing, child care, and so on. She takes from me and does all the things that years of group house living have taught me ought to be done by every adult for themselves. And she is quite good at noticing what needs to be done. Even such things as knowing that my sunglasses are in my pocket when I do not. I am not quite sure that I could get used to having a Housekeeper. Lisa says that they did not think that they could either, but that they have gotten used to it, or used enough to it. I suspect it is easier in a culture where having servants is common.

I spent the first half of my first day in Ghana sleeping. I woke up initially at 6:30, at which point it was already quite bright. Eventually went back to sleep, having not really slept on the way over at all, and woke up when Lisa got back from work at two. By then it was bright and hot. We then left to go swimming at a resort in Nungua near Teshie. We get a cab, and I quickly learn that Ghana, or the Accra area anyway, is bustling and growing. There is tons of construction, and the traffic is horrendous. The road from Tema to the resort in Nungua was two lane and bumper to bumper, with no stop signs or traffic lights to give any break to traffic on side roads, requiring people on them to be extremely pushy to get onto the main road. Overall the driving is not that bad - while you see outrageous things, they are caused by road conditions and the traffic, not by inherent insanity like in North Africa. Still, there are many accidents. We saw many, and on my last day in Accra, Amadou did not come to pick us up because he had been in an accident. Apparently he was fine, but the driver of the other car was injured. They blaimed cell phone use. (By the other driver).

Teshie, near the resort, is home to a famous coffin shop. This shop makes coffins in a wide variety of shapes, including airplanes, Heineken bottles, chickens, and just about anything else that you could imagine. It also has a quite nice craft store where I saw the best beads I would see anywhere in Ghana. Of course, I did not buy them, because I figured that I would see them everywhere and that I should look for a better price. Live and learn.

Other than an the beach resorts, and eating and drinking, there really is not a lot to see in Accra. The first day that I actually went into Accra, we went to the National Museum, which had some interesting things, but was sparse, had many replicas, and was somewhat poorly organized and poorly interpreted. I did learn some things, but much of it lacked context, especially dates. We also went to the market to buy cloth. There was stall after stall of great tie-dyed and batiked cloth, for prices so low they still boggle my mind. Fortunately we got a bit lost, so I also got to see the food stalls with the stacks of peppers, the bags of spices, the piles of meat, and of ground hogs (whole with their fur still on) and plates of giant snails in big purple shells that are a local delicacy, though not one that will be found in a restaurant (nor the groundhog for that matter), not to mention all the hubbub and madness that makes markets what they are. From the market we went to the tailor to have clothes made. I did actually have grand plans of buying cloth and having clothes made even before I got here, but the truth is that I probably never would have gotten it together on my own. Fortunately when I got to Ghana Lisa inspired me with all the great clothes that she had had made and also knew exactly where to go, so it was easy. And the results, when I picked them up later, were marvelous.

I did go to beach resorts. Twice to La Palm Royal Beach Hotel, once for drinks after Aburi and once to swim. A shocking spot in the midst of where it is really, but their pool is marvelous and it is only $3.60, and I just cannot claim that I do not like it. I tell myself that it does help the local economy, and the wages, cab fares, and expenditures by the guests who do venture into the city surely do that, while at least some of the food served there must be local. And I assume that there are taxes. But I would be willing to bet that it is not Ghanaian owned.

Later in the trip, I went to the cultural center in Accra, which is a large collection of people selling crafts. On getting there, I swiftly decided that I should have done my shopping elsewhere. The sellers there were extremely pushy, so much so that I left places where I wanted to buy things rather than deal with it. Moreover, their quoted prices were so high that even I was moved to bargain and in two cases got them down to less than half the initial asking price without much effort, making me wonder if I was not still paying too much. Other places that I bought, the prices were reasonable enough that I either would not bargain or would offer to knock them down by small amounts just for show. Still, in retrospect would have shopped a little more other places and would have covered more of my Christmas shopping if I had a clearer idea what the cultural center would be like. From there, though, we went to Okasan for lunch. Okasan is in an almost perfect spot, overlooking the ocean at a point where it seems like there is nothing else nearby at all, despite the fact that we walked off a busy city street to get there.

Ghana appears to have more manufacturing than other places that I have been in the third world. Not only is there mining (gold) and agriculture (chocolate), but things are made here. Latex is big, since it is grown here, but other things are manufactured here as well. Lots of people have jobs, but most of them are not paid much. Read something the other day that said that the average yearly wage is about $400 a year. And while $400 will buy a lot more in Ghana than it will in the States, it won't buy that much more. Inflation was apparently bad at times also, since the largest bill they had at the time that I was there was a 5,000 cedi note, which was worth about 65 cents. I realized after I changed $200 that I would have to carry my backpack, because my money would not fit in my purse.

Evidence of cheap labor is everywhere. The pizza place has someone to open the door for you. The grass, even the huge lawns at the resorts, is cut with a machete. Clothes are washed by hand, and made by hand. And, of course, everyone who makes much more than the standard level has a housekeeper.

In addition to manufacturing, commerce was everywhere. There are some glass front stores, many of the standard concrete boxes with the garage door on the front that were so common in Bolivia and North Africa, though the doors are usually big swinging metal things rather than garage doors, and a large array of shacks and tables on the side of the road, plus hundreds of people that walk along the cars stopped on the side of the road and attempt to sell a wide variety of things to the people stuck in traffic. I saw one man walking down the street selling pants from a stack that he carried on his head. Even extremely substantial things like carved wood furniture, the swinging metal doors, or concrete posts might be sold by the side of the road. The inefficiency amazes me. When I need concrete posts, do I remember which part of the highway I saw them on? Will the guy selling toilet paper come by my car on a day when I am almost out? Which of the eight thousand tables by the side of the road might have the item I am looking for? It boggles the mind. Of course, there is the market, where these things are gathered together, and there are American style supermarkets, or at least one of them.

People are everywhere, and they really do carry things on their heads. Not just the traditional water jar or basket of fruit, but a boxes of bread, the equipment for a manicure shop, a bunch of fluorescent bulbs, five gallon paint bucket, spring rolls for sale, or whatever else they happen to have. Perhaps because of this everyone has marvelous posture and the women have this incredible walk that I would assume drives men crazy. The men carry things on their head also, but it just does not give them that walk.

The trip to Elmina started at the United States embassy in Accra, where Bill had a medical appointment related to some nasty food borne illness that he had picked up in Benin. We were late, so late that we showed up about the same time as the driver, who was to meet us at 9:30, well after Bill's appointment. As a result, I found myself loitering outside the embassy with the driver, watching security check the undercarriage and engine of every car that went into the compound, and wipe them down, I guess for explosives. I also chatted with the driver, who was curious about life in the States. He was interested to learn that there is a part of the US that has weather and plants like Ghana, and no snow. He wanted to know about driving in the US, and about education and how important it was. He told me that it is very important in Ghana if you want to get anywhere.

Eventually I went into the embassy, which was about like getting into an airport terminal except that I could not bring my camera at all. All just so I could use a bathroom that was clean enough, but cramped and had no toilet paper. That was actually the first place that I had to break out my private stash, and I thought it was kind of ironic that it was in the US embassy. As it turned out, I would use only one more bathroom that had no toilet paper, and that one had some outside the stall that I could have used had I noticed it on the way in. The guidebooks are uniformly negative about Ghanaian bathrooms, but my luck was consistently good, at least in part because I was able to be rather picky about where I went to the bathroom.

Getting out of Accra was a lot easier than getting in and soon we were out in country and village, and termite mounds five feet high and higher. Eventually, we came to a point where we were obviously in beach towns. Though we had been driving near the ocean the entire time we could now see it, along with the thatched huts of the fishermen on the far side of the road. In other words, we are into resort territory, complete with palm trees, tropical flowers, and cabins facing the ocean.

Our cabin is back a ways, split between two rooms, with the bathroom spread in pieces along the back. The living room is the front porch. The resort has a small pool and a big walkable, but unswimmable, beach. That, unfortunately, is common. The ocean along the length of Ghana is apparently plagued with all sorts of nasty tides and undertows and it is often not safe to swim, or only a very small portion of a large beach will be marked as safe for swimming. Since it is also true that many of the beaches are close to large groups of people living without adequate sanitary facilities, some of whom, it has to be presumed, use the ocean instead, I was perfectly happy to do my swimming in pools while I was there.

Hardly anyone here seems to be old. In part that is good - after all, 30 year old women in Bolivia looked old, and Ghanaians would not seem to have that problem. But apparently it is not just that everyone is well-preserved, but also that there is a very low life expectancy. A diet thing, at least in part. There is food - it is so green here that I cannot imagine famine. But they do not eat vegetables, other than plantains, yams and the tomatoes and peppers that they put in sauces, and the diet is mostly meat, food wad (kenkey, fufu...) and oil. Lots of oil, and the oil of choice, logically, is palm oil. That alone is probably enough to kill them.

The first place we went in Elmina, actually in Cape Coast, was the Internet Cafe, not that any of us would be addicted to e-mail or anything. From there we went to the restaurant that is in St. George Castle in Elmina for dinner. It is in a perfect spot for a restaurant - high on the castle overlooking the ocean, a fishing village, and the area where the new boats are carved. We were the only patrons there for the night, which usually makes me nervous, but the food was fine, if unexciting, and the setting was perfect. Adding to the ambience was a 'cultural club' which was practicing drums and dance. Very cool. In fact, we saw drumming and dancing many places we went, much of it solely for the pure joy of it rather than to entertain others. There was also dancing to recorded music, and I had to laugh when we went through a small rural town and one house near the road had set up its yard as a disco, complete with huge amps. I don't think that village even had electricity - they must have run the system on a generator.

On our first full day in Elmina we headed out for one of the major inspirations for this trip - Kakum National Park, which is famous for its canopy walk. All the way from Elmina to Kakum we saw children in school uniforms walking to school. It is good to see that so many go to school - though out this far we did not see many over the age of 12 - but they seem to walk extreme distances to get there.

The canopy walk at Kakum is longer and shakier than the one in Myakka State Park in Florida (the only other one I have seen) and definitely scarier. Basically each of the sections, of which there were about 6, is a series of planks on some support, the whole thing about a foot wide, suspended in a net hung from cables that are strung between huge trees. If you could get your foot smack in the middle of the plank while walking it went pretty well, but even a little bit off and you were catching yourself on the ropes at the top of the net. Soon became convinced that I would have rope burns before the whole thing was over. But I managed and the views were spectacular. Felt sorry for Bill and Lisa, who had to deal with Miranda, who quickly decided that she wanted to be carried rather than walking. Of course, carrying her put them off balance, making it even harder to stop it from rocking. The path up to the walkway went through some nice woods as well. But there were places with tons of ants. They would be in huge lines across the path and we would jump over or walk around as best we as we could, but people ended up getting bitten. On the way out we stopped to eat lunch and I found two ants on my sock - located largely because one of them had managed to bite me right through the sock.

After the canopy walk the guide did a nature hike in which she discussed the uses of various trees, including that tree with the weird high roots that we have seen in Florida, saplings of which are used for the sticks to pound fufu. The bark of mahoghany is used for male potency. The tree with thorns (not the pink flower one) the bark of which is supposed to cure asthma. And ebony trees, which they call elephant comb because elephants use it to scratch their butts.

We stopped in the visitor's center on the way out. It had some good, environmentally correct displays. One display had the question "What do you do when elephants trample your crops?" Four possible answers appeared on liftable panels over text that outlines the outcomes of those choices. Essentially, three out the four would be, at best, temporary solutions, while the fourth, killing the elephants, would diminish the tourist trade that brings money to the village. Tried to buy a coke after that, but they just don't have the tourist trap thing down yet and had only malts. The malts are put out by the beer companies (Guiness and Amstel) and are basically stout without the alcohol and with more sugar. It is promoted as a health drink because of the B vitamins and I suppose it is an improvement over beer itself, or the local water. We also went to the gift store and I bought a post card for my injured co-worker and a round-headed figure for a friend. According to a display at the National Museum, Ashanti women who wish to become pregnant strap these figures to their backs the way that they would carry a baby. The display also said that they are designed with the features that the Ashanti consider beautiful. I have to assume that they exaggerate some of them, for surely a human born looking like these dolls would be in for a very tough life.

After consulting the guidebook, we headed off for Domana Rock Shrine, which is about 30 km past Kakum. The roads went to dirt and became increasingly potholed and went through villages that were seriously rural. These villages had mud and mud bricked houses with thatched roofs and looked like okay places, surely not wealthy places, but ones where people were not desperate and made a sustainable if simple living - far different from the slums outside Elmina and Cape Coast. One of these villages, perhaps it was Ankaako Junction, had a chop house called "Don't Mind Your Wife Chop House." (A chop house is a cafe/diner where the local food is served cheaply. They, unlike the other restaurants, are patronized more by locals than by tourists). This is somewhat typical of Ghanaian business names. Typical at least in that it is bizarre. Elmina has a little shop called "Friends today, Enemies Tomorrow," and there are tons that reference god. I.e. "God is Great Sound," and "All my Strength Comes From God Fashions." Not to mention "Thy will be done Licensed Chemicals." Many buses, tro tros and trucks also have religious slogans on them. Saw a truck that said "God is Merciful" on the front, which would be a grand last sight as it ran you over.

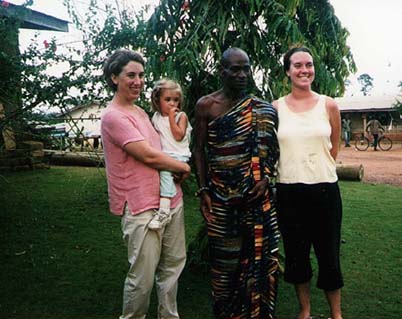

We arrived in Atobiasi Junction, which was a village of about 1500 people, and, on asking directions to the shrine, were told we would have to meet the chief. The chief lived in a simple enough house, but had the best yard in town, with grass, hibiscus and other flowers. The chief himself sat dressed in old pants and a t-shirt drinking a large beer. With him were a man from Accra and a couple of other people. We greeted him, sat on his porch and he asked our mission and whether we had any questions. He also sent someone to give us some cokes, and learning that we were Americans, sent for the local obruni (white person, or foreigner), who, turned out to be the Peace Corps volunteer who is there to help them develop the shrine as a tourist destination. She sent for a tour guide and the chief explained that the shrine had been found by his great uncle or some such relative and that it had totally freaked all of them out and they had concluded it was the realm of some sort of forest sprite they have which sound to be in the realm of leprachauns or elves. He also said that he had been a doubter but some event that I could not quite follow through his accent had convinced him. He also said that visitation to the shrine had been limited by all sorts of restrictions - against wearing black, against wearing sandals, against going there if you had sex the night before - but that these had been lifted in the hope of building tourism. He planned to reinstitute them later. And honestly I do not see why not if there is notice, but I'm not sure how they would enforce that last one. Anyway, he said that he had gotten the idea for tourists and had gotten the Peace Corps to send a volunteer and generally talking to him I got the impression that he was a good chief. The tourist business is definitely in its infancy though, the PC volunteer said that they get eight or ten people a month. Of course, that was exactly what I wanted to hear, since I love getting off of the beaten path and away both from tourists and from the areas that have been ruined by them.

Anyway, they said that it was 7 km to the shrine and that we would drive most of the way and then walk the last km. So we set off. The road almost immediately became significantly worse. There were horrible ruts, mud holes, a creek, or what seemed like one, and decrepit log bridges, one of which had a gap wider than a tire running the length of it. I kept expecting the taxi driver we had hired for the day ($20) to denounce us as lunatics and refuse to go further, or at least to demand more money. But he drove all the way to the end and we walked the last piece, which was more like a mile than a kilometer and much of it either uphill or down, but was a nice hike in itself.

The shrine is inside an area created by a gigantic rock that is balanced on three or four other huge rocks. The fact that such a huge rock (no less than 50 feet long and 15 tall) was balanced that way was odd enough, but was made much odder by the fact that there are no other rocks of any size at all anywhere near there. None.

The shrine itself is fairly conventional - a conveniently shaped rock against which people had left various offerings including Coca Cola and liquor. Not exactly spectacular. But the place itself was amazing. We walked through, and as we came back to the front the guide offered a chance to see it from the top. Unfortunately, doing so required a climb up the rock using vines to pull yourself up as you walked up the rock face. The guide and the taxi driver did it, and Bill and Lisa tried and could not, but I knew better.

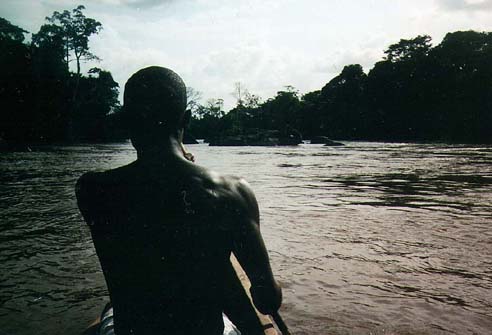

On our way out, the guide (actually a substitute guide since the usual one could not be found when we were in town) asked us if we wanted to go to the river to see if the water had subsided enough to canoe down it. He said that would be 2.5 km down to it and 2 km back to the car from the end point. He also said that some people had gone about four days ago and the river had been too high. Given the heat and the length of the first kilometer we hesitated somewhat, but eventually decided to do it. This part of the hike was quite pleasant, rather flat, and I doubt that it was even one kilometer, much less 2.5. At this point I should mention that the guidebook actually says that Ghanaians are lousy judges of distance. The path led to a tiny rural village near the river and accessible only by boat or on foot, with a few neat mud and thatch huts, goats, chickens, some children, and a young woman preparing gari (gari is a coarse-grained roasted, grated fermented flour, made from cassava and used as a staple food in a similar way to ground rice).

We went down to the water and hung out while the oars were brought, which boat to use was debated, and how much to charge was settled, and Lisa played catch with a bevy of children who had come to stare at us. Then we were rowed down the river in a tippy canoe - us, the guide, the taxi driver, and the two rowers. The river was wide and had occasional, very small rapids.

The walk to the car was also shorter than predicted, and went through a cocoa forest. Some of the nuts were ripe. Inedible in that form of course, but the lumps of chocolate are surrounded by a sweet white goo that can be sucked off of them. They said that they get about $1 a kilo for the chocolate, which they partially process by breaking it out of the hull and drying it. Actually that was how I understood it, but now that I think of it that sounds high. There was Ghanaian chocolate on the bed when we got back that night. Not bad but not great - too much wax - perhaps because it is made for such a hot climate. But clearly their specialty is not in production. Nevertheless I will take some back.

On the way back up we stopped in an even smaller village. No one was home, and it had only a few buildings, a nice vegetable garden, and some orange trees. Lisa had slipped getting out of the boat and hurt her hand and was feeling light-headed so she asked if she could eat an orange. We all ate one, and at the time they seemed like the best oranges ever, though technically, they were only okay, not being sweet enough to qualify for perfect. Lisa wanted to leave 2000 cedi to pay for the oranges and the guide tried to stop her saying that because the villagers were not there it did not matter and that the people were superstitious and that finding strange money might scare them, so Lisa left it with an orange peel so they would understand that it was for the oranges and not magic. As it turned out though, we met a woman from the village on the way up to the car and it was explained to her so there was no danger of misunderstanding.

While we gathered at the taxi Lisa said that this had been her best day in Ghana. It had definitely been mine so far, but it means a bit more when she says it. Of course, I had to contemplate the possibility that she spoke too soon as we had a long way out on a crazy road. And in fact the car did get stuck and it was necessary to get people to help us to free it from the mud. They were the proof that this place is not ruined yet as they were reluctant to take money for their help and did so only at our insistence.

After getting unstuck we went back to the chief's house to take photos. We found him better dressed than he had been, but still not in his ceremonial garb. He went and changed and we took photos in his yard before the hibiscus. From there we went to Hans Cottage Botel, which has a restaurant over a small lake that has crocodiles. They sell bread which you can throw in the water to attract the fish, which in turn attract the crocodiles. Or that's the theory. We did see two pretty small crocodiles and one large one and we sat at a table right on the lake next to two trees that were absolutely full of egrets, with a few parrots for good measure. They made an incredible racket until the sun went down and then preened themselves in unison and went to sleep. I ordered the chicken curry, which I had been thinking all along would be a Ghanaian curry, but of course, Ghana was a British colony and it was Indian curry. Very good though. I also tried another Ghanaian beer. I had one at Elmina that was quite drinkable and thought this was the same one but it was not and was not nearly as good. The one at Elmina was Club, a nice crisp pilsener and this was Star, which just tasted like cheap beer to me. I eventually decided that Gulder was the best of them. But as a general rule, Ghanaians are beer drinkers and the quality of the beer reflects that.

Came back to the hotel and went to the bar with Bill for a glass of wine. We met a man there from DC who had vacationed in West Africa for the last five years. In Ivory Coast first, branching out as that situation became impossible. He did not think much of Benin, but seemed to be enjoying Ghana. Then the music started and conversation became impossible.

The next day we went to see the two castles, Cape Coast and St. George's. The taxi driver from yesterday, who we had arranged to hire today as well, showed up with a different cab, saying that yesterday's cab no longer works. I feel responsible, though my legalistic mind tells me that I am not, and I make all sorts of rationalizations about how he could see the road as well as I could and knew the car better, had the right to stop, had gained knowledge of the place that would help him with other tourists and got to have as much fun as we did for free, not to mention that we did pay more than the agreed on price in light of the length of the day and the roughness of the road. All of these are true, and also within the understanding of the driver, but that does not change the fact that he, who can afford it least, is the one that will pay for whatever it is that drive did to the car, and to some extent, rightly or not, he will resent it. And it is hundreds, then thousands, of little dramas like that one that make up the weirdness that is tourist areas in the third world.

Today, however, the driving is easy. We go to Cape Coast castle first. A castle like any other except that unspeakable things happened there. Today, you can walk around it and it is concrete from this century and hard stone walls around big empty rooms. You could be anywhere, in any number of forts and castles around the world that look like this, but instead you are standing in a spot where thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions, of people suffered and died in horrible conditions. Cape Coast and St. George's castle, which is in Elmina started as trading posts - administrative offices for the trade in ivory and gold. But as the slave trade got big, and started to pay more than trade in gold and ivory, and started to disrupt that trade by taking the workers and otherwise making work impossible, they became the holding pens for human cargo. We stood in dungeons where slaves were held for six weeks waiting for the next boat. Five hundred women over two areas, more men in a series of rooms together. Food distributed in such a way that people ended up fighting over it. Light only from small, high openings. Nowhere for the women to 'ease themselves' as the guide put it, but where they were. No place for the men to ease themselves but the 'wash room', surely the most bizarre use of the word I have ever heard. It was rinsed by rainwater, but apparently it did not rain enough, because the feces would accumulate over a foot deep at times before rain would wash it down a gutter that ran through the other rooms. (This was next to the ocean mind you, it could have been set up to rinse at high tide like at the fort at St. Augustine). For the life of me I cannot understand how anyone lived through it, especially when you add the heat. Heat because it is the tropics, heat from all those bodies. You would think that the walls would scream. But they are just walls.

We also looked at the punishment cells - one for soldiers who disobeyed, with light and a slot for food, one for slaves who had rebelled and were condemned, with no light, none, no ventilation, and no food. They were taken out when they died. Maybe not right away either so a person might be left to starve to death in total darkness with a dead body or so. As a person who gets twitchy in total darkness, that really freaks me out.

We came out from the dungeons to the same sunny and peaceful tropical paradise that we had left and got lunch at the castle restaurant. This one was not on the castle but next to it, open air, right next to the ocean, and the food was relatively good. We then went to the internet cafe and then Lisa and I went to St. George's while Bill took Miranda back for a nap. We missed the tour at Elmina and just wandered around it, which allowed us to walk around the battlements and look over the ocean and the fishing wharves. We did look at the men's dungeon though, and the original door of return was still there, short and narrow, so as to let only one person out at a time. (At Cape Coast it had been replaced by huge swinging doors to allow a symbolic return of two slaves whose bodies were brought back and reburied in Ghana). Also at Elmina the women apparently had a courtyard where they could get out in the air at least some of the time, and if they did not the dungeons at least opened on to it.

Cape Coast had a large museum on Ghanaian culture generally, on trade, and on the slave trade and the diaspora. Elmina had an exhibit with photos and art and information. Both were very interesting, and worth reading in their entirety. Interestingly the Elmina (and at least one other that I have seen, though it may not have been Cape Coast) made a point of also recognizing the beneficial things that Europeans brought to Ghana, crediting them with such things as education and masonry construction. It seems inadequate in light of what was done. Not only to those who were made slaves, but to the entire region. Something that I had never appreciated before is the wreck that the slave trade, or more accurately, the massive increase in the slave trade spurred by demand in the new world, devastated the economy and culture in the places the slaves came from. The explanation often given for the fact that knowledge of Ghanaian culture virtually starts with the slave trade is that the Ghanaians prior to that did not write their history or experiences down. That is true, but the fact that there was no oral tradition and few continuing traditions from which to construct it, hardly anything that is ancient at all, surely must also be blamed on the societal crisis that was the slave trade. And while people in that society did plenty to enable and carry on that trade, it was the Western demand that made it happen.

Another interesting set of facts that I learned in the Cape Coast Museum is that 1/3 of the slaves were from Islamic countries or Islamic influenced areas, and a small number were from Christian countries. Also 1/3 went to Brazil, 1/3 to the Carribean, and 1/3 to the Americas with the "smallest number" going to the US and Canada. That "small number" is between 1.5 and 2 million from 1620 to 1860, no small number at all, but it does show facts at odds with the impression that one would get in the States.

It is interesting to see the different approaches taken in different museums to the fact that the local chiefs cooperated in and profited from slave selling and that much of the actual capture was done by Africans. No one denies it, which would be difficult. But the focus varies from the dispassionate "it was done" attitude in which the crimes of the Europeans are described to the slant that everything was just an eden here until those evil Europeans came and got us guns and stirred up wars so that we could get slaves for them. In between is the truth - this was not eden, but already had wars and sold the captives as slaves. It was a slave trade on a completely different scale, and of an entirely different type than what the European trade became. Had that difference been clear, would it still have happened? Who knows? But what I do know is that an Eden could not have been turned into the hell that this area was. Not in the way that it was, and probably not at all. It was the conflicts in the existing society that opened the door for the dismantling that took place.

There were other lighter notes at Cape Coast Castle. For example the "communications room." Today that brings to mind a room full of computers and phone equipment. At the time, it was a room with a window that looked over to the fort where there was a lookout. If they lit a torch the castle was under attack. Also, in the town of Cape Coast we saw a sign for "Police Experimental Day Care." Not exactly where I would be sending my child.

The museums also listed many things now in the country that had been brought there by trade. The extent to which that list included things that are major staples in Ghana amazed me. Pineapple, cassava, maize, tomatoes, cabbage, oranges and many other foods were not native here but were brought from elsewhere.

We spent the last night of our time in Elmina pretty calmly, having dinner at the resort, watching a dumb movie, and writing. We never really got to go into the town as much as I would like. Elmina is a quaint little town, with old buildings, little shops, and a bunch of Posuban shrines. Posuban shrines are huge concrete shrines put up by Asafo companies, the patrilineal military units that are a feature of Akan society. The shrines are reputedly ancient, but are changed over time as fashions and moods change. We saw two of them from the cab when looking for a place to buy socks. They are tall, faintly oriental looking structures with statues and decorations on them. One had statues of Adam and Eve.

Our driver was late in the morning so we got a late start on the way to Kumasi and were further delayed by a police stop when we learn that Osu (the driver) has forgotten to bring his license. At the next police stop the officer looks in the trunk and then he comes to my window. The driver opens my door and tells me that the officer just wants to say hello. The officer greets us and leaves. Later Osu tells us that the officer had wanted a bribe "since you are traveling with white people." Osu had told him that we had not yet gotten our luggage, but of course a look in the trunk had made clear that was not true. So Osu told him that we had the money and if he wanted a bribe he had to talk to us, and he guessed that when he faced us he was intimidated. The whole thing gave me second thoughts about the wisdom of traveling by Volvo since we had not been stopped at all on the way down in the Toyota. Fortunately, however, while there were plenty of checkpoints on the remainder of the ride, we were not stopped again. I noticed at subsequent stops, however, that the checkpoint signs are sponsored. There was the latex foam police stop, and the last one had an ad for the Pink Panther hotel. Street signs were also sponsored and had large ads on top of them, my favorite being the ones for batteries that had huge replicas of the batteries on top of them.

Driving around Ghana I am reminded of the guidebook saying that accidents are common. In Bolivia the reminder of accidents was all the shrines on the side of the road. Here the reminder is that the car is still there. I saw a couple that had been there so long that they were completely rusted. Other cars sit, occasional parts removed, waiting for nature to take its course. I concluded today that the reason that one should not drive at night, as the guidebook said, is not because people don't use their headlights (everywhere I have been they do use them) but because it is harder to see the foot deep pot holes in the dark.

First in Kumasi and then later in Accra I saw signs saying there was a traffic light test and to drive carefully. If the test was to see if anyone would stop, in Kumasi at least I would have to say that the answer was no.

Finally we arrive at Lake Bosumtwi. Lake Bosumtwi is sacred, though the details of the beliefs surrounding it are fuzzy, at least to the people who write guidebooks. The typical starting point is Abono, but we instead went to an hotel off to the side of the lake. The driver explained that in the town people would come around and pester us but at the hotel that was not allowed. The guidebook did in fact mention this problem. It is an endless problem in Ghana - it would be better for the entire village if it did not have this reputation, but there is no obvious way, consistent with freedom, to curtail it. As for us, we went to the hotel and hired an hour boat ride for 140,000 cedis, about $16.80. It was very relaxing and the lake was beautiful. One of the boatmen told us a bit about the history of the lake, a legend of some hunter, but his accent was so thick that I really could not understand him. I do know that the lake was in fact created by a meteor. It is 10 km long and at least 74 meters deep, and it is getting bigger, leaving the stumps of huge trees well in from the shore. Part of the beliefs about the lake bar the use of the traditional boats used in the rest of the country. The locals instead use boats that are essentially thick boards they straddle and paddle with little boards. Our boat however was clearly metal (which apparently was traditionally banned) and had an outboard motor. The fishing nets are smallish nets attached to bamboo poles that are strewn about the lake. Some so new that they are still sprouting greenery. The guide said that the lake is full of tilapia, and we saw some fresh caught while waiting for the boat. There are 21 villages along the shore of the lake and they apparently drink the water after boiling it. There is an awfully lot of particulate matter in it for that, but I saw no evidence of more than two power boats, and most of it looked organic.

We decided to leave right after the boat ride as to make the ride to Kumasi, to the extent possible, in the light. On the way out Lisa exclaimed about a huge tree, remarking on how majestic they were and how they towered over everything in the forest. Osu responded "We use them for matchsticks." We then came to the city of Kumasi, a large city, and at least in the dark, comparable to Accra. I noticed, however, that a different cloth is popular here - a white cloth with black designed. I believe that the traditional forms have the patterns stamped on.

Coming from a lake full of free range tilapia, I was thinking tilapia, but Lisa was jonesing for a pizza, so we went to three places that had pizza. At two it was "finished." So we decided to eat Indian food instead since Kumasi had an Indian restaurant that the guide book rated the best in the country and we had passed it while looking for pizza. When we got there it turned out that they had pizza and would serve it, but by then everyone had decided to have Indian. It was good, but not the best I have had. Could very well have been the best in Ghana for all I know though.

A note on food. Ghanaians eat snails. Not escargot, ground snails. Really big ones. Amadou says that they are like tongue - no bone. My personal feeling is that my usual drive to try every new beast that I run into will have to take a break on this one. Speaking of Amadou, Lisa told me that on the way to work one day BBC had someone talking about the health benefits of drinking one's own urine and about how it was done all over the world. Lisa squelched the urge to say "Oh gross they do not." and instead asked if anyone else had heard of that, only to have Amadou reply "Oh yes the first urine of the morning is especially good."

I am starting to notice that Ghanaians apologize a lot. Sorry may be the most common word in daily use. They even apologize for things that could not possibly be their fault. A Ghanaian student in Kakum apologized when I walked into an over head branch. Osu apologized when Miranda's ear medicine made her cry. And so on.

We stayed at a guest house in Kumasi - It was about $15 a night, but had no cable TV, only four Ghanaian channels. Enough for me to realize that Ghanaian TV moves in real time. It makes for some boring TV, especially when you are not used to it. Even the thing that appeared to be a Spanish telenovella translated into English was in real time. And it was really bizarre that I have been sitting here for about an hour wishing that I had gotten a bottle of water before coming to the room only to learn that the refrigerator has water in it. I should learn to look around me more closely. Also, as in all cheap hotels, the staff was loud in the morning. And the breakfast, which in Elmina had been a variety of breads, fresh fruits and fresh-squeezed juices and other breakfast foods, here was plain sweet white bread and really nasty margarine. We supplement with Nutella and apples and it suffices. The guest house also had one other problem that I had never run into before and did not think to check - the shower had only cold water. On the plus side the bed, like every bed that I slept on in Ghana, was perfect. They are hard foam - very firm, but they give, just enough, in just the right places. I want one.

We were up early and the driver was even later than the time we gave him, which was already too late. We head to the cultural center, look at a lot of crafts and learn that the museum was open Sunday after all, but is not open mondays until 2 pm. Not expecting it to be exciting enough to wait three hours for it. So we went and had beans, fried plantains, and fried fish for lunch. Very traditional Ghanaian food and very filling. As was the fufu in spicy chicken soup that Lisa had. These together with fufu (or other food wad) in groundnut soup, and Jollof rice, which is rice cooked with chicken or other meat and tomato, are pretty much the heart of Ghanaian cooking. Well, those, plus the hot pepper sauces.

We then went to Bonwire where there is a shop where they make Kente cloth. Unfortunately, while Kente cloth is famous the world over, and is made all over Ghana, this is the village that gets the travel book write up on it. As a result we are beset by village boys immediately, wanting to introduce themselves, exchange cards, sell us things. It is a small village, they could probably put a stop to this, or control it. But they do not, or maybe this is what they have decided to allow. The boys do serve the purpose of showing you to the workshop. The weaving process is pretty cool. There is plenty of stuff for sale there. Lots of Kente is cool stuff, but I have trouble envisioning it in my life.

When we go outside one of the kids has made a bracelet in the African colors with my name on it. I had been told about this scam, but had never run into it. Told him there are lots of people named Kathy and I did not ask for it. After some hemming he gave it to me. Of course, it is as useless to me as it is to him. I have no problem with African colors, but I am not likely to start wearing my name on my wrist any time soon. Maybe when I'm senile, but it will open me up to candy from strangers when I wander off.

From Bonwire it is an almost endless drive back to Accra. The road is bad, and busy, and is goes through many villages, some nice, some not, and some mountains, by Ghana standards, anyway, which were nice. There were even more and nastier wrecks along the road. At least one was recent, a bus with passengers still standing on the road and a tow truck backing up for it. Another truck looked fresh and too big to leave there, though the tow truck was the first evidence I saw that some actually did get hauled away.

On the way home we stop and get pizza. It is six hours since we last ate but I really don't feel that I have burned it off and pizza on top of it makes me feel that all the food I ate today will be a permanent part of me - palm oil and all. The pizza place is next to a high end electronics store - big screen TVs, stereos, etc. They are both in a shopping center than has an iron gate to close it off and its own security guard out front. A woman opens the door for us as we approach the pizza place, waiting for Miranda to get up the steps. At first I think that she is just really polite, but it turns out that she works there. Another sign that labor in this country is far too cheap. How do you fix that? It is not that no one is paid well. The houses in Lashibi, the electronics store, the people I see in the cities, all attest that some Ghanaians have a lot of money and that others are perfectly comfortable. But the majority are not. How does an economy create enough work, real work, that peoples labor can be a commodity that pays enough to support them? This bothers me, but I have no answers. The tourist dollars are a trickle down at best. Most of the money goes to the resorts, many of which are not Ghanaian owned. The money to the villages is indirect - a few people have more money to spend. Some tourists may come into town and buy direct but the swarming limits that greatly. The swarming is born of desperation, and the desperation can't end until tourism dollars come to the village (or some other industry - but which is more likely in the short run?), so the very thing that you are trying to get rid of is what inhibits even a partial solution.

Pretty much everyone who lives in Ghana is Black. In fact, black skin, black hair, and brown eyes are so common as a description that driver's licenses also list head shape so as to provide some ground for differentiation. I had assumed that in a country where almost everyone is Black, the government is run by Blacks, and all of the businesses are owned and run by Blacks that people would not specifically identify as Black - that race would simply not be a relevant factor. After all, I do not think that most white people in America identify as white. But Ghanaians do identify as black, and when I reflect on it, it is not so odd, given the history and the fact that world power is white. And of course there is the fact that in Ghana, identification as Black (and as African) is unifying, while identification by tribe or language group would not be, so there is a positive aspect to it. I have not determined where in the mix tribe or language group and nationality fall. It does seem that perhaps tribe, or language group identity, is stronger. There are enough language groups that English has been maintained as the official language, though Ghana was one of the first African countries to shake colonial rule.

Unlike North Africa, where the primary identity was Muslim, religious identity does not seem that strong here. Not that people are not strongly religious and quite open about it, but many different religions and combinations of religions are practiced in what appears to be an atmosphere of general tolerance. Religion is strong though. Everywhere we went I saw the symbol, Gye Nyame, which I heard everyone tell means "Accept God." But it turns out that they really were saying "Except God" like it said on all the trucks, except that the full meaning is that there is nothing except the Omnipotence and immortality of God.

Even stranger than the identity thing, which really, on examination, is not so inexplicable, is the fact that many people here appear not to be comfortable with being Black. Most people are quite dark, much blacker than most African Americans. But the billboards and TV ads on Ghanaian TV are full of hair straighteners and skin lighteners, and the models chosen for ads are lighter than the population. The wife (or sister) of the Chief in Atobiase Junction told me that her skin was "too dark." Personally I love the dark skin and probably look too long at the young men with their shirts off. But really, how, in a Black culture, does this sort of self hatred take root and hang on? It makes no sense to me.

We set out on the late side, read e-mail, and set off for Aburi. Aburi is up in the mountains over a beautiful green valley. The botanical gardens are cool, but extremely poorly interpreted. There are no maps that tell you what is there or where it is. There are a ton of paths, none of which make clear sense. We found a trail through a portion of the garden devoted to medicinal plants that actually had very thorough signs listing all the uses for the plant in various cultures, but could not find either the beginning or the end of the trail through it, only the middle. There was also a tumble down pavilion in an overgrown part of the woods with a view of the valley over the trees, but no path to it, and no explanation of what it was. While down at the very end of the gardens we started to hear thunder and ended up skipping the more established part of the gardens because it started to rain. We went to the craft store at the garden then went out into the village, which has a lot of stalls with woodcarving. Very low pressure by Ghanaian standards, and in retrospect I wish I had bought more than I did, but was afraid that I would have trouble packing it and bringing it home, and really, that may have been true. By this time it was pouring and we were dashing from place to place. Because of the rain we decided to skip the cocoa farm (the first in Ghana), but as soon as we started south it was bright and sunny again. So we went home, after a detour for beers at La Palm, had wonderful Moroccan food, and the Accra part of my trip resumed.

And that is it really, in perhaps not the most organized possible fashion.